Making Public Inquiries

How Do Two Public Policies Help the City Cash in on Land and Air—and Assign Our Future to Speculative Urbanism Along the Way?

Everywhere we look, intensified land development and worsening housing affordability seem to be the dominant features of our present and future life in the city. In the northern metropolitan region in Taiwan, housing affordability has deteriorated, and fast. In 2002, in Taipei City and New Taipei City, the housing price to household income ratio, a measure of housing affordability, was slightly above six in both cities. By 2020, it had deteriorated to 14.85 for the former and 11.86 for the latter. Meanwhile, between 2012 to 2020, land prices increased 14.28% in Taipei City and 26.52% in New Taipei City, meaning housing affordability has worsened much more. Despite the rising land and housing prices, local authorities have continued to churn up new plans, development zones, and apartment buildings. But they are all more of the same—luxury high-rises whose prices top whatever came before them.

With an eye toward a more socially just urban future, our scholarly and civil engagement work, individually and collectively, has investigated the relationship between planning, public policy, and the politics of land development. This webpage draws from this line of ongoing endeavors and focuses on two public policies—Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing. We unpack their technical and regulatory workings and tease out how they shape the relationships between people and land, public and private, present and future, and rich and poor. Our goal is to mobilize public inquiries in order to facilitate a politics of land that is more just and equitable.

An Urban Studies Foundation Knowledge Mobilization grant supported the creation of this webpage as well as three virtual public forums on land and social value on July 30 and 31, 2022.

Urban Transformation, Speculative Urbanism, and Public Policy

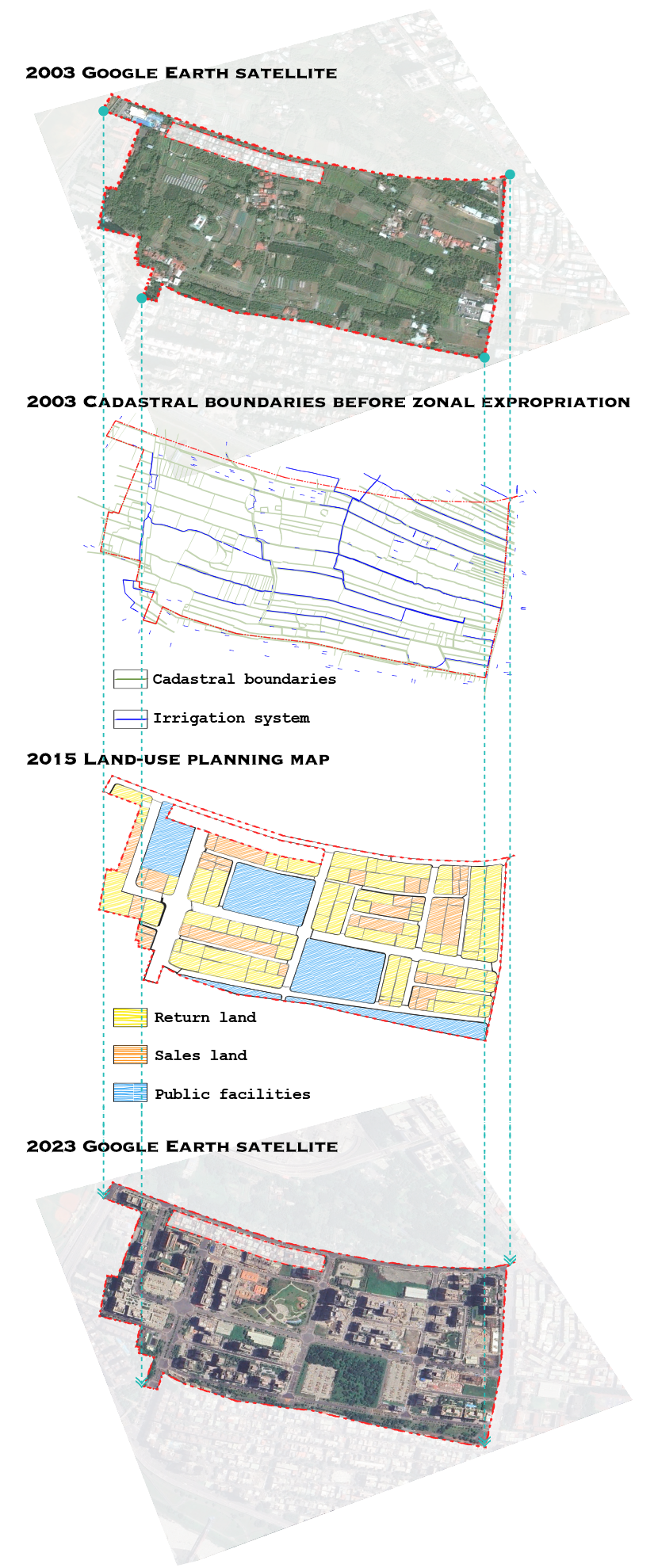

Since 2015, new development of luxury residential apartment buildings has completely transformed the Central North area in New Taipei City. Gone is the nearly 100-acre farmland of orchards, bamboo groves, vegetable beds, and small rice paddies and the irrigation channels that once kept the land and air moist and cool. In the rapidly growing and nearly built-up Xindian District, Central North was one of the very few remaining urban farmlands, and now it is permanently lost. In its place are new high-rises that command some of the highest housing prices in the city. An average-size apartment of 100 m2 (about 1,076 sq ft) easily costs about $710,000 USD, 21 times the city’s average household income. 1Between 2023 and 2024, the average unit housing price in Central North is 750,000 NTD/ping or about 7,100 USD/ m2. One ping is about 3.3 m2 and one USD is about 32 NTD. For an apartment of 100 m2 (about 30 ping, a common size in Taiwan), the total cost is about 21 times of the average household annual income in New Taipei City or 15 times that of Xindian District. In 2022, the average household income is 1,050,476 NTD (or 32,827 USD) in New Taipei City and 1,474,634 NTD (or 46,082 USD) in Xindian District.

The two sets of policy tools that have created the Central North today—Zonal Expropriation (quduan zhishou, 區段徵收) and Density Bonusing (rongji jiangli, 容積獎勵)2Density bonusing is the term commonly used in the literature and by planners. In this webpage, “Density Bonusing” in fact includes both Transfer of Development Rights (TDR, called rongji yizhuan, 容積移轉 in Mandarin) and other density-based measures in Taiwan. —have ushered in an urban transformation process that is inseparable from and even co-constitutive of speculative urbanism.

Zonal Expropriation targets so-called underperforming land uses—farmlands, open fields, industrial sites, etc.—and makes them legible to real estate capital investment through its land assembly techniques. Density Bonusing further intensifies land development by granting real estate developers additional buildable floor area beyond zoning limits in exchange for privately funded public benefits. Zonal Expropriation in Central North was speedy and extremely profitable. It took about only four years to complete since its official start in 2014, and it generated a net profit of almost $674 million USD for the city government.3The official net profit is 20,234,102,619 NTD. See New Taipei City Government, 2018. Appendix – Final Report of Zonal Expropriation Project in Central North Area in Xindian, New Taipei City. At the time of writing, all 18 real estate projects that we surveyed, which were either already built or under construction, used Density Bonusing.

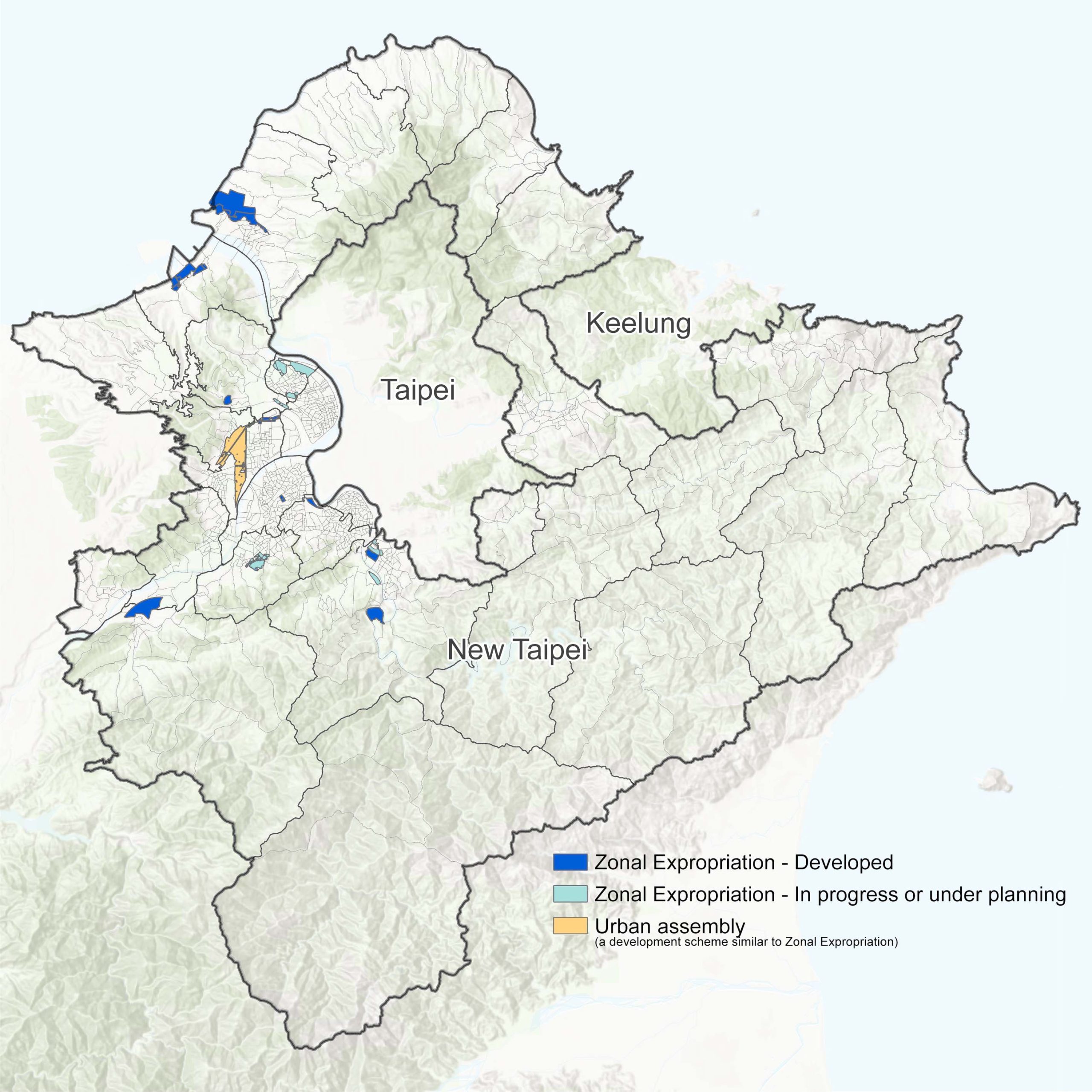

Central North is also a window into the city government’s playbook for real estate-oriented urban development. Several more Zonal Expropriation projects are either in progress or being planning. The city’s expansive and development-friendly Density Bonusing measures ensure that “found money”4In a report in The New York Times, air rights are described by a real estate professional as “found money.” The Great Air Race, The New York Times, February 22, 2013. can be minted out of thin air for both the real estate sector and the local authority.

New Taipei City (formerly Taipei County) has a population of about four million people. It has rocky coastlines in the north and mountainous inland areas in the southwest. Zonal Expropriation projects have rapidly transformed urban farmlands, industrial land uses, and manufacturing factories in the city.

Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing are powerful shapers of the city’s urban present and future. The form of urban spaces, the type of buildings, the cost of land and housing, the profit margin of real estate capital, the relationship between public and private, the politics of land, and the state of equity and justice all hang largely on how Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing dispose of land. What is at stake is whether land is treated as a source of money to be extracted while speculative urbanism accelerates, or as a social relation that enables a way of living that is more economically equitable and socially desired. Choosing one of the two opposing urban telos that shape how we use and value land should be an intentional decision that we collectively make through practices of deliberate democracy.

We need more public inquiries about Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing because they are public policies that affect our urban lives.

Yet, it is not always easy—in large part because both Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing involve fairly technical operations with regulatory complexity. Their inner workings and their enabling role in speculative urbanism are often inscrutable to the public.

For example, local authorities and development experts often rationalize, and, in fact, expand the use of Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing on the basis that they provide public benefits. In one such instance, a lot of 3.7 acres on which a social housing project of 1,070 rental units sits is obtained through Zonal Expropriation in Central North.5The provision of land for social housing through Zonal Expropriation in Central North was, in fact, a highly precarious process. The original land use planning did not include any land area reserved for social housing. However, is social housing provision the end that motivates the operation of Zonal Expropriation in the first place? Or is it luxury property development instead? If the former, why is only 3.7% of the total area set for social housing, especially given the high profitability of Central North development? Who decides what counts as a public benefit and therefore is legible for density rewards? Why is profitable real estate capital investment the policy framework within which public facilities are provided? Is the city whitewashing speculative urbanism by deflecting questioning of their disingenuous claim of privately funded public benefits? What is the cost of speculative urbanism? And what segments of the population are more likely to bear the burden?

We should ask these kinds of questions relentlessly. This webpage is a small step toward that mobilization.

photo/Wei-Ying Chen

HeHe HaoHao (禾禾好好) consists of three buildings. One of them (foreground) is entirely for social housing, for which it receives 2,875.06 additional m2 buildable floor area.

photo/Wei-Ying Chen

QuanYang DaXi (全陽大璽) receives 4,790.8 additional m2 buildable floor area beyond what the existing 240% FAR allows. Its lot size is 9980.83 m2 , greater than the 500 m2 minimum lot size set by the land use ordinance.

Land – Zonal Expropriation – Speculation as Its Inner Workings

In the 1980s, facing grassroots resistance from private landowners affected by government-led development projects, and lacking a big enough budget to compensate affected landowners fully at the market price, land officials of the central government came up with a new scheme to turn large swaths of so-called under-performing farmland or industrial sites into urban development. The scheme is called Zonal Expropriation. The name makes it clear that it involves the use of state power (i.e., “expropriation”) for large-scale land development (i.e., “zonal”).

The core design of Zonal Expropriation is to valorize land as much as possible so that revenues generated from land sales can pay for development costs, if not produce a surplus profit. Proponents argue that it is financially self-sustaining and a no-loser tool. In reality, Zonal Expropriation has been a most important off budgetary revenue maker for municipalities.

Land reorganized through Zonal Expropriation is grouped into three functional categories. Return Land (dijiade, 抵價地) is used for in-kind compensation. Affected landowners have the option to receive 40% of the original land area after development. Proponents praise that Return Land is cost-saving because the local authority is rid of the enormous compensation in cash payment, that it avoids displacement, and that it gives original landowners a fair share in future urban development. Public Facility Land (gonggong sheshi yongde, 公共設施用地) is used for locally needed infrastructures such as roads, parks, and schools, or other major regional-scale facilities, such as transit stations, university campuses, and public housing. Sales Land (biaoshoude, 標售地) is sold to the highest bidding real estate developers to generate revenue.

In many parts of the world, a similar mechanism called land readjustment has been used to transform vast peri-urban regions into schemes such as smart cities, tech cities, or new towns, impacting thousands of ordinary people and their livelihoods.

Zonal Expropriation has erased 100 acres of farmland and replaced it with luxury residential high-rises that make up Central North today.

Land brokers: Speculative land assemblage

In reality, speculative land brokering and transactions are key to the inner workings of Zonal Expropriation. Land brokers, working on behalf of real estate developers, buy farmland parcels from small farmers, assemble them into larger holdings, and transfer the titles to real estate developers who later build luxury residential projects. To understand how Zonal Expropriation and speculative land brokering go hand in hand, we need to first unpack the mundane, but crucial, details of technical operations and regulations. Embedded in them is a calculative space that real estate developers exploit for profit.

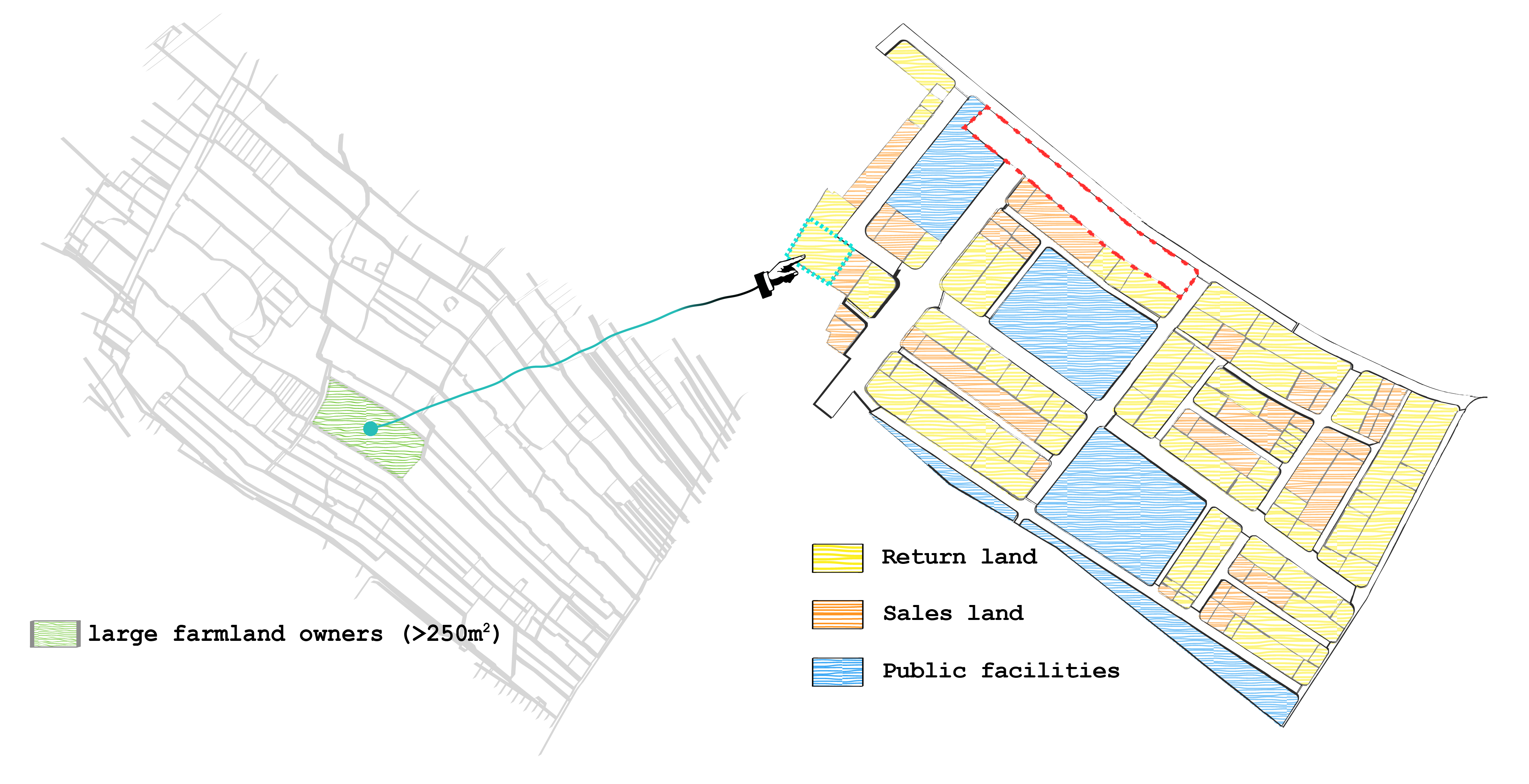

The land use ordinance of Central North stipulates that the minimum lot size for development is 100 m2. This means a landowner—referred to as dizhu, or 地主 in Mandarin—needs to hold a farmland parcel larger than 250 m2 before Zonal Expropriation (i.e., 40% of a 250 m2 original parcel is 100 m2 in return land).

Zonal Expropriation is a land assembly technique operating on the condition of land valorization. In Central North, landowners of more than 250 m2 have the option of in-kind compensation.

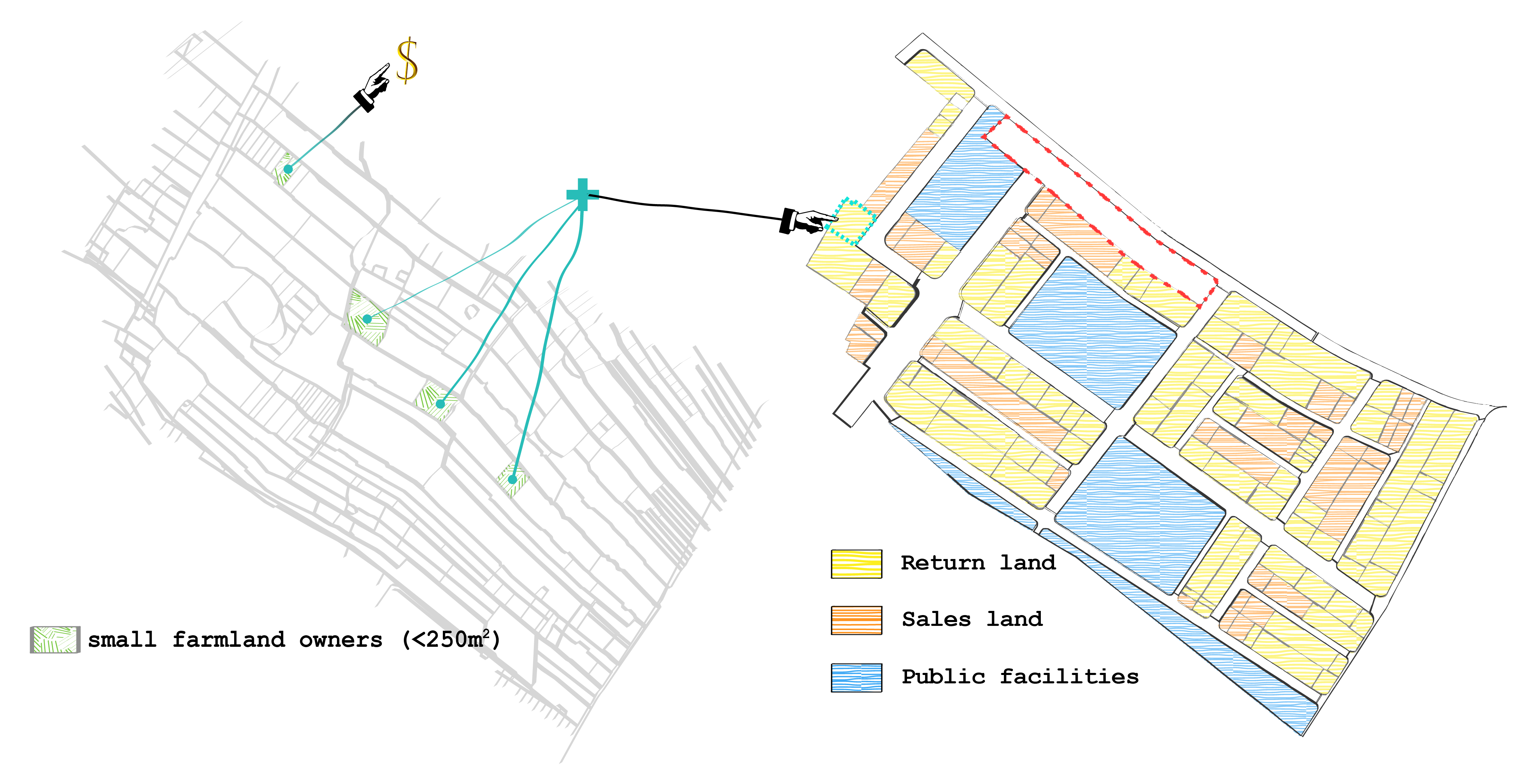

Small dizhu of less than 250 m2 have two options. They can choose to receive monetary compensation and relocate elsewhere, or several small dizhu can enter into a share-holding (gongong chiyou, 共同持有) agreement so that collectively they meet the 250 m2 threshold to be eligible to receive a return land lot as shareholders.

It should be made clear that where the developable return-land lot is located after Zonal Expropriation has nothing to do with where the original farmland parcel sat, and small dizhu can pull widely scattered farmland parcels into a share-holding agreement as long as the sum area is larger than 250 m2.

Small landowners either relocate elsewhere after receiving monetary compensation or pool several parcels into a share-holding agreement.

Real estate developers: New dizhu (地主) gaining a foothold in land development

In 2010, about four years before Zonal Expropriation, there were 574 private farmland parcels owned by about 2,000 farmer-dizhu, many of whom were either small landowners or family members who held land collectively. Small and fragmented farmland holding is a common phenomenon in Taiwan.

The operational design of Zonal Expropriation opens small landholdings to exploitation for profit making. Because as long as real estate developers cobble and transfer enough farmland parcels under their ownership, they become a large dizhu that is entitled to receiving 40% of what they “owned.” Developer-dizhu is an intermediary through which real estate capital churns up profit in land in the future. This is exactly what happened in Central North.

The total number of original dizhu dropped from about 2,000 to about 1,290 at the beginning of 2014 and further down to 299 by the time Zonal Expropriation officially began in July 2014. It is impossible to know precisely how many of those 299 dizhu were real estate developers, their proxies, or the original farmers. What is certain is that real estate developers gained a firm foothold in Central North even prior to Zonal Expropriation. As we will see, Density Bonusing furthered the acceleration of ownership turnover in Central North.

Air – Density Bonusing – A Catalyst Heating up the Land Market and Prices

Speculative land practices in Central North have also been encouraged by Density Bonusing. By allowing real estate developers to build taller, bulkier, and larger developments beyond zoning limits, Density Bonusing increases their profit margins. In return, real estate developers are asked to provide certain privately funded benefits to the public. Density Bonusing is a kind of entrepreneurial deal-making struck between the real estate sector and the local authority.

Both sides try to cash in on air with Density Bonusing. But at what cost, and who pays?

In the literature, practices as such Density Bonusing are referred to as “land value capture,” an area attracting a growing interest from both researchers and practitioners. It is widely agreed that in an era of urban neoliberalism and financialization, local communities and the general public often get the shorter end of the value capture stick. In Central North, a heated land market and rising prices, which impacts all of us, is one consequence of Density Bonusing.

Central North has a 240% FAR (Floor Area Ratio6FAR is a ratio of the total buildable floor area (for example, in square meters) to the total lot area.) as the land use ordinance stipulates. The city government, however, has created at least five measures for density bonuses. If a building meets criteria for a Smart Building (zhihui jianzhu, 智慧建築), an additional 3% of 240% FAR is granted; a Green Building (lujianzhu, 綠建築) gets 5%. If a developer assembles a development lot larger than 3,000 m2, the Large-Scale Reward (guimo jiangli, 規模獎勵) grants 15% of 240% FAR and 10% for 1,500 m2. The city’s TDR (Transfer of Development Rights; rongji yizhuan, 容積移轉) program7For a detailed discussion of the TDR program in New Taipei City and its impacts on housing prices and urban spaces, see Shih et al, 2019. Where does floating TDR land? An analysis of location attributes in real estate development in Taiwan. Land Use Policy, 82: 832–840, and Shih and Chang, 2016. Transfer of development rights and public facility planning in Taiwan: An examination of local adaptation and spatial impact. Urban Studies, 53(6): 1244–1260. is another source from which the developer can purchase additional density. Finally, for every square meter that is given to the city government for use as Public Facility (gonggong shehi, 公共設施), the developer receives two square meters back. Public facilities are defined broadly, and include community centers, government office spaces, or social housing. The Large-Scale Reward is the most generous among these density bonusing measures.

Illustrations showing types and percentages of density bonuses used by each project.

Source: Google Maps, SINYI.com.tw, Leju.com, and flickr.8From left to right, the photos were provided by 0207 Chen, Sun Yu-Ting, Kevin Cheng, SINYI.com.tw, Hyatt Pan, Hyatt Pan, Hyatt Pan, Hyatt Pan, Guo Ren-Teng, Brad Wang, Zheng Ren-Teng, 0207 Chen, Leju.com, 0207 Chen, and Zheng Ren-Teng.

At the time of writing, all the 18 projects in Central North that we surveyed used various combinations of these five measures. The actual FARs range from 271% to 384%, are higher than the 240% FAR set in existing land use ordiance, rendering zoning limits pretty much irrelevant. In fact, the use of density bonusing has been so commonplace in real estate development that it is to be expected, rather than an exception.

This map shows the 18 real estate development projects surveyed in Mi Shih and Ying-Hui Chinag’s research on density bonusing. Move the cursor on top of each pin to see the type and quantity of density bonuses used.

(Data sources: New Taipei City Urban Planning Review Committee and https://www.leju.com.tw/)

Against the routinization and normalization of Density Bonusing, let us problematize this policy for a moment. Who decides what is a legitimate basis for receiving extra density? For example, as it stands right now, the local planning authority grants large-scale development projects the most generous Density Bonusing.9See Shih and Chiang, 2024. A politically less contested and financially more calculable urban future: Density techniques and heightened land commodification in Taiwan. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 56(6): 1753–1770. But why does a big-lot development deserve more policy incentives than a green building, given climate challenges? Or, why is social housing not the top candidate for receiving the most generous density reward, given the widespread lack of affordable housing in the city? It is also most costly, both in money and time, to meet the criteria for Green Building and Public Facility measures. The differential treatment in policy does not seem to be based on any sound, consistent, and convincing rationale.

Amplifying the ad-hoc nature of Density Bonusing is yet another question: Who bears the brunt of costs? “Minting money from thin air,” or what density bonusing allows is sometimes colloquially referred to, as no free lunch. The designation of FARs often bears some connection with the projected population density and development intensity in the area. And as a conventional practice in planning, infrastructure’s carrying capacity is often calculated on the basis of these FAR and demographic parameters. Higher density means more people, cars, traffic, and more demand for existing infrastructures. The city will need to pay for these not immediate but real costs somehow, someway.

Density boosterism

In Central North, real estate developers were eager to buy farmland parcels prior to the official start of Zonal Expropriation in anticipation of future profit. How aggressively they hunt farmland is in large part influenced by how bullish the anticipated future return of profit is. Because the total buildable floor area determines the number of salable units, more density bonus means more revenue. Density Bonusing stimulates real estate developers’ land hunts by boosting their profit calculus.

To illustrate the boosterism effects on farmland purchase prices of Density Bonusing, we mimic the method real estate developers use to perform cost-revenue analysis. It is called the residual model. This is a calculative practice widely used in land appraisal and real estate development finance analysis.

Developers’ cost-benefit calculus

Let us start with the no-bonus scenario. The existing FAR is the basis on which the total salable housing units are estimated. The developer then calculates the total sale revenue (SR) and the total construction cost (CC). After deducting the net profit return (NP) set for the project, the difference (LP, or “the residual”) is what the developer can use to purchase farmland.

Total buildable floor area, which is determined by FAR, plays a major role in how much capital (i.e., LP) the real estate developer is left with for farmland purchase.

Not every density is the same

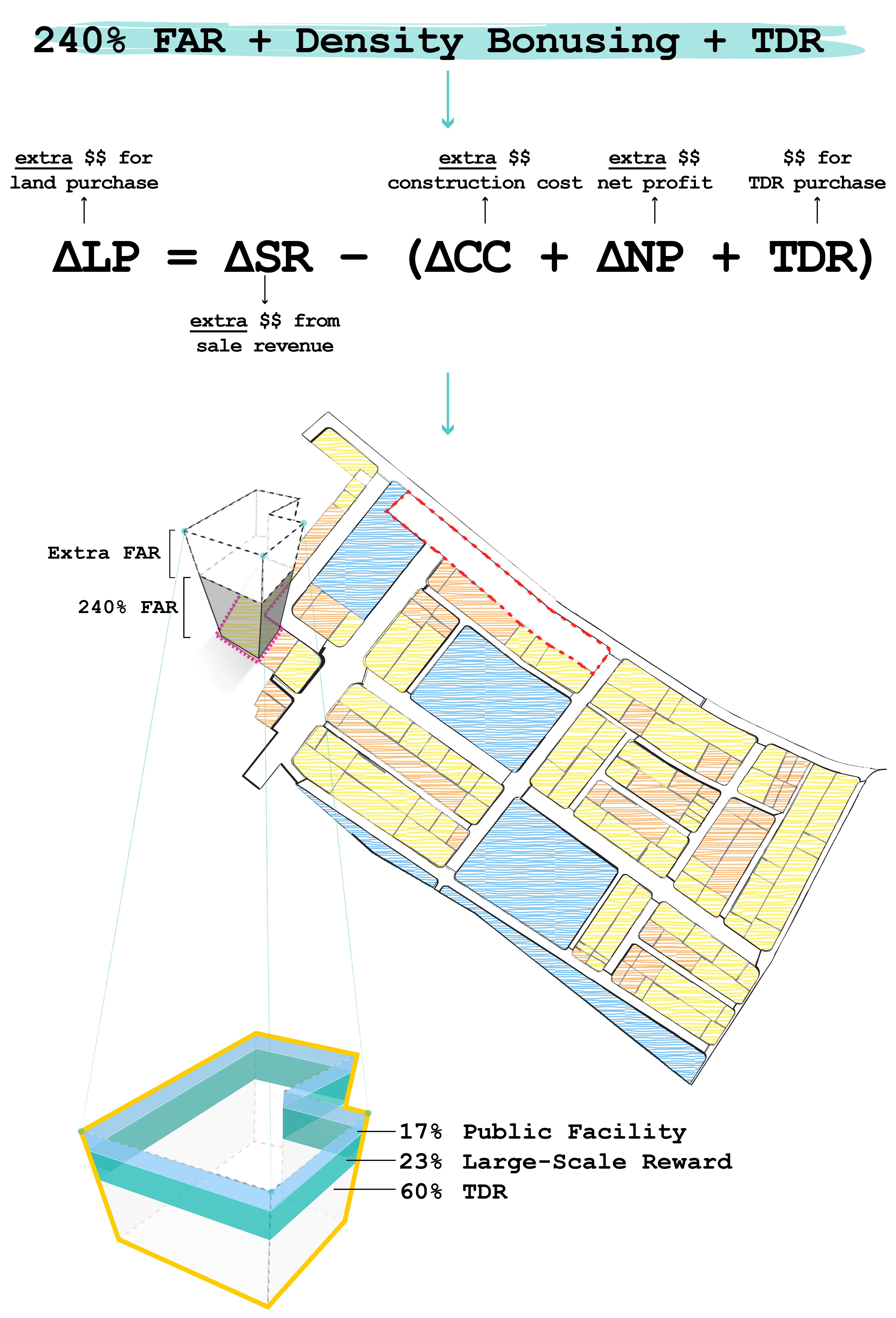

Now, let us consider the bonus-boosted scenario. Every term in the previous calculation remains, but now with an increment (i.e., the delta sign), reflecting the impacts of additional density. Not every density, however, is the same—some are more profitable while others are more costly to build.

Density Bonusing boldens real estate developers’ farmland hunt by allowing them to pay for a higher purchase price (i.e., ΔLP). Above illustration is based on the case of the Bordeautx II.

Large-Scale Reward is the most generous, hassle-free, and preferred bonus. Unlike Green Building, which requires specialized construction designs and materials, or Public Facility, which involves time-consuming negotiation over specifications, Large-Scale Reward is “a bonus with no strings attached,” as it was described to us by one professional consultant who had firsthand knowledge of density bonusing. Because there are no additional construction costs (other than those incurred by building more floor area) or complications, Large-Scale Reward is the greatest profit booster among all bonusing measures, while Green Building and Public Facility are the least profitable and popular.

ΔLP: Heightened land hunts, a heated land market, and rising land prices

Density largess has real consequences. Chief and crucial among them is that real estate developers are financially incentivized to buy farmland more aggressively with higher offer prices exactly because they expect to offset those costs in the future with more salable units and the larger profit margin afforded by density bonusing. In fact, this larger appetite for farmland is exactly the speculative land brokering behaviors that Large-Scale Reward induces—act now to assemble a bigger farmland lot for generous density bonuses in the future.

Since only the sum of land area matters—i.e., farmland parcels can be as scattered as possible—land brokers, working on behalf of real estate developers, canvassed Central North to seek out any possibility for a sale deal. Land brokers were emboldened and their offers were daring. Real estate developers, land brokers, and real estate professionals whom we talked to told us that, in about a two-year period, the farmland purchase price in Central North went from 3,300 USD/ m2 and reached as high as 5,400 USD/ m2. While farmland prices went up, the number of dizhu went down, from about 2,000 to 299 in about a three-year period. The important implications are that real estate developers, through land brokering, had already gained a foothold in Central North even before Zonal Expropriation official started. In addition, it is almost certain that high housing prices will be the way in which developers will recuperate those high land purchase costs.

City’s Urban Future

If the story we present here convincingly demonstrates that, in addition to the loss of the ecological values and an alternative way of life associated with urban farmland, the way our public policy treats land is problematic, that land practices are speculative, and that private profit plays an upper hand over public interest, how do we do better?

To help forge a collective problem-solving process going forward, we offer a few ideas and suggestions as a starting point.

We need a meaningful movement that shifts land development from a club-like field dominated by a few actors—government officials, professionals, and dizhu—to a public domain where inquiries, debates, and deliberations are welcome, more frequent, and taken seriously. Our city’s urban future is at stake if we leave land development as a bureaucratic and private matter.

We need to significantly expand institutional and political spaces for public participation in debates and inquiries about land development and the role of public policy so that there is meaningful engagement of local communities and the larger public. We need to relentlessly ask questions such as who decides how land is to be disposed, through what process, for whose value, at whose cost, and to what end.

To help the public make these inquiries, information surrounding Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing should be released as widely available, user-friendly, open data prior to real estate development. For example, the workings of Zonal Expropriation often appear quite technical with regulatory details to ordinary people. Residents often only realize the outcome of density bonusing in their neighborhood after, not before, the fact. People should be able to know how much taller the building adjacent to their homes will be, on what grounds a particular density bonus is granted, and what the impacts might be before it is approved and built.

There should be a serious overhaul of the current Density Bonusing measures. For example, why is large-scale development more generously incentivized by the policy? Whose interest does Large-Scale Reward primarily serve? What is the impact on housing affordability and land prices?

The bottom line is that public benefits are both material and procedural. What counts as a public benefit cannot be a decision made solely by government officials or planners, whether it is out of professional preferences, entrepreneurial ideology, whimsical thinking, or a bow to the pressures of real estate capital. Without a public engagement and deliberation process to safeguard and test “publicness,” preferential policy treatment of certain market behavior (such as large-scale development) almost always leads to private profits, not public benefits.

Fundamentally, because Zonal Expropriation and Density Bonusing have kept land and housing markets heated and speculative, we need a public mobilization and engagement process to challenge and change the politics of the status quo. For example, Zonal Expropriation has long been treated as a landed source of fiscal revenues for the local authorities. Success is assessed by the size of net profit generated. We need a new politics of land that puts other intangible, non-financial, social values—such as environmental and ecological values, farmland protection, greater provision of social housing—at least on the same footing with profit making.

How we treat land holds a crucial link to the kind of urban future that lies ahead of us. Making public inquiries is a small but crucial first step in reimaging and remaking that urban future.